Truss Rods (2/2)

Truss Rod Recommendations from a Mechanical Engineer

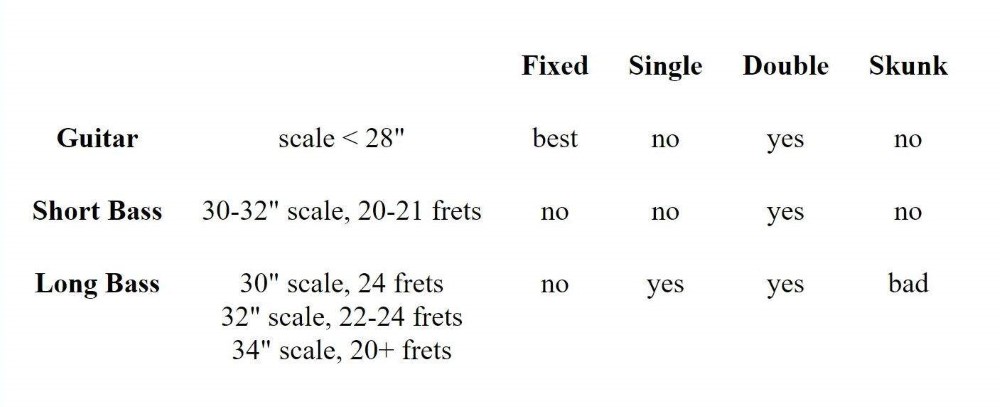

Summary:

A double-acting rod is appropriate for any situation. That does not mean it is required in every situation, although it is the only choice for a short bass. For guitar necks, a fixed rod is better, as it is cheaper and will never require adjustment. A single-acting rod is only appropriate for a long highly-stressed neck. There is no reason to use a skunk stripe ever.

Truss Rod Recommendations from a Luthier

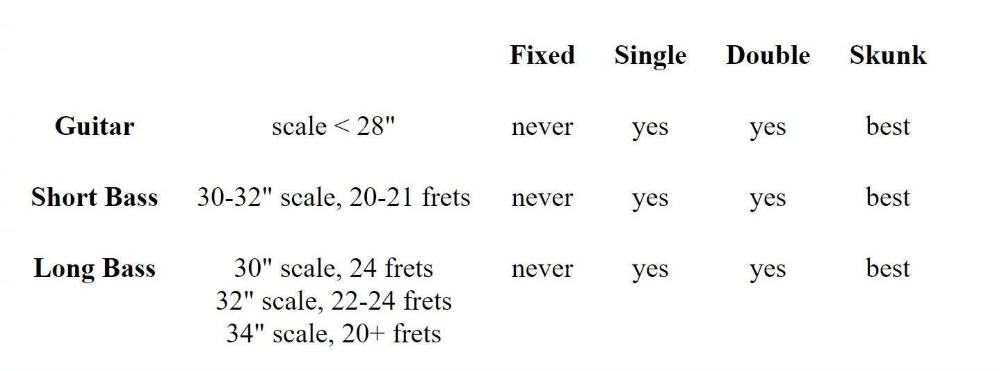

Summary:

This is more like the standard industry answers. Never use a fixed truss rod, because adjustability is a major marketing point. How well a rod works in any particular situation is irrelevant. The skunk-stripe is the best because it was thought of in the 1950s 1940s 1930s Dark Ages, and progress is bad.

You really can't consider the skunk-stripe to be a single-acting rod. A single-acting truss rod creates a very small backward force at the head perpendicular to the neck, and that's all. A skunk stripe doesn't do that. Instead, it creates a strong compression of the wood lengthwise along a curved channel. That has the secondary effect of bending of the neck backward, along with god-knows-what other effects - not a single action at all.

To go along with this, from an engineering point of view, a bolt-on neck attachment is superior to glued-on or through-neck attachments. Bolt-on allows for adjustment/replacement of the neck. Adjustment of neck angle can be done simply with the use of shims. If the screws are adequately tight, the joint is stronger than the wood itself.

Through-necks are at least likely to be straight, but they have no adjustment and are totally unreplaceable. The "joint" is simply the continuous wood, which is as strong as ... wood - no gain there, and if it is badly designed, could actually be a weak point. This is not that far-fetched - Gibson headstocks are one continuous piece of wood with the neck, and they snap off with alarming regularity.

Glued-on necks are the worst; there is no guarantee that they are straight, and they are neither adjustable nor replaceable. Crooked glued-on necks get sold anyway. ( Hello, Tennessee! ) Glue is in no way stronger than steel screws, in fact, over time it could prove to be significantly weaker.

There is no difference in "tone" or "sustain" between the three designs. Note that this engineering assessment flies in the face of all guitar mythology. Guitar necks should be glued on ( with animal-based Hide Glue only ) because luthiers didn't have screws in the Middle Ages when electric guitars were invented. Oh wait, that doesn't make sense. But it's luthiery !!!

The bolt-on design allows the angle of the neck to be adjusted independently. With a through- or glue-on neck, there is no way to adjust the angle. If such an adjustment is needed, the only resort is to misuse the truss rod. Now you're attempting to change the angle of the neck by bending it into a curve. That's not the same thing, and, except for the smallest of adjustments, results in a neck that is mysteriously bad. Not only that, but if it is a skunk stripe, you are placing the wood under even greater stress, which could have bad long-term effects. That is probably the reason for all those old necks twisting.

Leo Fender knew nothing about luthiery when he built the Telecaster, and he did it all "wrong". The one mistake he had to correct was not having a truss rod in the neck. It is unfortunate that he copied the skunk-stripe rod from Gibson rather than the solid steel bar from Martin. If that were the case, luthiers today would be crowing about the tonal superiority of the Fender solid truss rod. Danelectro proved that solid rods work - 60-year-old Danelectro guitar necks are as straight as the day they were made. Of course, when Fender scaled-up the guitar into a bass, he kept the skunk-stripe, and the rest is history.

Hats off to Rickenbacker for using an almost-modern and far superior design from the start. They almost got it right, they just made it too flimsy. Instead of the 3/16" round I used, RIC used a 3/16"x1/8" flat, not nearly as strong. In addition, the flat is only threaded on two sides, making it much more prone to stripping. These are the reasons why RIC truss rods are so tricky to adjust and prone to failure, and why it takes two of them in the bass.

In fact, I happened to have the old girl out, so here is a look under the truss rod cover. The nuts are on the lower rods, you can barely make out the tips of the upper rods bearing against the crooked aluminum shim. Note that the shim is not pressed against the wood - the lengthwise forces in the rods are completely internal. You can see how heavily they beveled the ends of the rods to get the thread-cutting die started on the rectangular shape.

The other end of the rods are simply a bend, just like mine, which is why you can slip the rods out when they are slacked. I did that and Dremeled-out a bit of wood behind the nuts so I could slip a 1/4" wrench over them. Much easier to adjust now, with no risk of rounding-over the nuts. If one of these rods ever broke, I could make a replacement pretty easily.

For all their mighty price tags, Rickenbackers have a lot of cheap features. John Lennon's 325 didn't even have a full set of dot markers !!! How much do those cost? I'm not saying they aren't beautiful high-quality instruments, but they're not all they're cracked up to be. Case in point here - why did they cheap-out on these truss rods?

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .